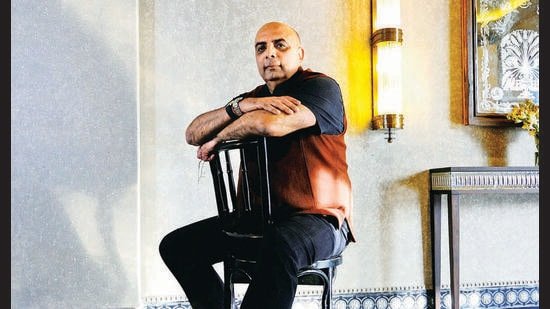

Fashion designer Tarun Tahiliani isn’t mincing his words. At 62, with 37 years at the top of the game, there are no “Hmm” moments. He doesn’t sit on the fence with his opinions. Indian brides today? They’re a confused lot, he says. Showstoppers on the runway? That must stop. The best route for promising young designers? They’re better off working for bigger brands than running a business.

Ouch. Ouch. Ouch. Indian fashion isn’t used to such truth bombs. It’s a world of anonymous gossip accounts, endless collabs, poor tailoring covered up with sequins, flattering HNIs, and flashing dazzling smiles even when you’re going broke. So, it helps that Tahiliani is the OG (his Tarun Tahiliani label turned 30 last year) and he’s seen more styles come and go than we’ve added to our moodboards. We asked him about what’s moving the needle in the business, whether we’ll ever look past bling, and what’s stayed the same. He’s thorny. Try to keep up.

Sense the pattern

Tahiliani wasn’t born into fashion. His father was an Admiral in the Navy, his mother was an engineer. His first job: Selling oil-field equipment. “I was losing my mind there,” he recalls. His heart lay in more creative fields, but “fashion designers were regarded as glorified tailors”, he says. “My father almost had a stroke when I told him I wanted to study fashion.”

He did anyway. And in 1987, at age 25, he opened Ensemble, India’s first multi-designer retail store, with his wife Sailaja. The world looked a little different then. “If you wanted stylish clothes, you went to Fashion Street in Bombay for export rejects, or you bought stuff from hippies in Goa.” He recalls picking up a pair of jeans from Anjuna, which his mom washed in boiling water before letting him wear them. “And if you had anything imported from Marks & Spencer, you were the coolest kid on the block.”

The rich commissioned the handful of top brand-name designers around then, for bridal wear – which cost about ₹25,000. Everyone else just went to the neighbourhood aunty who was good with patterns and charged ₹5,000. No Autumn-Winter or Spring-Summer collections. No Zara, no malls, no backless bustiers paired with a 2kg buckram skirt.

Tahiliani knew things would change. The National Institute of Fashion Technology had been set up the previous year, meaning there’d soon be a steady stream of designers for India’s growing rich. Meanwhile, Ensemble stocked his own early label, Ahilian; Rohit Khosla; Abu Jani and Sandeep Khosla; Anaya (a label by Anita Shivdasani and Anil Kapoor’s wife Sunita); and Neil Bieff (an American couturier based in India). The press called them the Fab Five of Indian fashion.

Bursting at the seams

Even then, Tahiliani, was thinking ahead. “I wanted to make structured drapes that fall beautifully on the body,” he says. Local tailors weren’t getting it right, so he studied fashion design at NYC’s Fashion Institute of Technology in 1991. “Those were the best days of my life. I was learning to create outfits without the pressure of selling them.” So, when he returned to start his own label in 1995, leaving Ensemble to his sister Tina, he was ready, and he knew India would be too.

Those early styles were groundbreaking. No one in the 1990s was working Western corsetry into the lehenga and sari. No one was making brocade dresses with a belt to cinch the waist in. By the following decade, as Indians got used to runway designs, beauty pageants and red-carpet events, Tahiliani was ready with pre-draped saris covered in Swarovski crystals, pearls and Chantilly lace.

In 2000, at the first Lakmé India Fashion Week, Tahiliani got a taste of how the industry would grow. His show had 500 seats but 1,600 people turned up. “I had to send apology notes to people who couldn’t get a seat. I hadn’t anticipated that kind of attention.” The world took notice, inviting him to show at Milan Fashion Week in 2003 – the first for an Indian. “We got so many orders from the world, but we couldn’t fulfil them. We still hadn’t figured out that part of the business.”

He got there. “For the first 20 years, I think I was just learning the best tailoring techniques,” he says. He’d eventually work out how to made stylish leather bandhgalas and lehengas that were under 5kg, and didn’t weigh down or bruise the bride. “I finally have the tools and I’m very excited,” he says. “A bride who comes to me knows she is going to be super comfortable in her outfit, that she’s going to look like herself and not be overpowered. Because I’ll never put heavy chunnis on her head.”

Knots in the tale

Tahiliani dressed British journalist Jemima Khan in off-white and gold, for her high-profile wedding to Pakistani cricketer Imran Khan in 1995. When Shilpa Shetty wed Raj Kundra in 2009, she wore blazing red TT. For her wedding to Anant Ambani in 2024, Radhika Merchant wore a TT lehenga-sari in silver and rose gold for one of her ceremonies. Each look was different, but all were unmistakably Tarun Tahiliani.

When he started out, he says that brides then were just grateful to get something well-fitted and beautiful. “You sold to a much simpler market, and brides were mostly happy with what you gave them,” he says. Young women today have so much to choose from that they’re “overwhelmed and just don’t know what to do”. They’ll see a celebrity’s white wedding and want a white lehenga, but if a red one is trending tomorrow, they’ll change their mind. “I tell the girls to be true to themselves and me, and to stay in their comfort zone. Don’t think of yourself as a character in a movie.”

It’s tough. Weddings do look like movie sets now – and are held in multiple locations. Families bring stylists along when they shop, to keep track of it all. “Oh my God! I have never seen anything like that,” says Tahiliani. He has made outfits with precious-metal threads and semi-precious stones. He is making one using countless real pearls, costing ₹90 lakh. It’s great for the wedding and other ancillary industries. But is bigger always better? “Not at all,” Tahiliani says. “When it’s so big, people are usually trying to project something. It’s how people arrive and announce their status in society now.”

Buttoning up

Thirty years on, we’ve gone from a single boutique and Fab Five designers to multiple fashion weeks, Indian designers dressing Beyonce and Cardi B, and Reels that break down who wore what heirloom jewellery. Bollywood and fashion are inextricably linked – one is threatening to eclipse the other.

Tahiliani says he works harder than before – long hours and even Sundays. Tina Tahiliani Parikh, his sister who runs Ensemble says “it surprises me how much he has pushed himself from when he started.” His team is young, many under the age of 35, who weren’t around for Indian fashion’s early strides. “They are very talented but also entitled and spoiled. If you ask them to do one extra thing, they think they are being exploited.” he says. “We didn’t have that option.”

What he does have is a global fandom and formal backing, things that would have astounded him 30 years ago. In 2024, Tahiliani sold 51% of his label to Aditya Birla Fashion and Retail, a conglomerate that owns Galeries Lafayette and Shantnu & Nikhil. It means he can focus on design, rather than being distracted by business, like he did as a fashion student in NYC. “Running a fashion business is a lot of hard work. The glamour part is just 20 to 30 minutes of the shows.” It’s still exciting. “I am still a babe in the woods,” he says. “It’s only in the last seven years that I’ve got all the tools to make well-structured outfits. From here, it’s going to be fun.”