As the government began implementing the scheme, the state has witnessed a striking political image: educated job seekers lining up for Rs 1,500 a month under a welfare programme rapidly emerging as a key plank in the run-up to the 2026 Assembly elections likely to be held in the next two months.

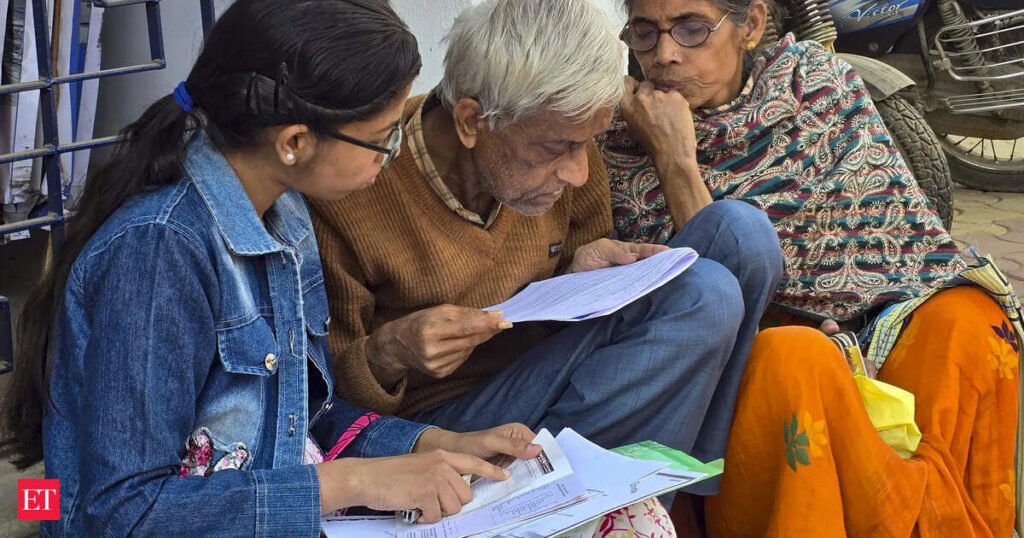

From Master’s degree holders in physics and mathematics, engineering graduates and students of computer science and chemistry to class 10 passouts, thousands of unemployed youths queued up across the state this week to register for the scheme.

Announced in the interim Budget earlier this month, the scheme promises Rs 1,500 per month to unemployed youths aged between 21 and 40 for up to five years or until they secure employment.

Though initially slated to begin in August, Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee advanced the rollout to April 1, a move widely viewed as politically significant as election season approaches.

With camps set up across all 294 Assembly constituencies and online applications now open, the initiative has triggered a statewide rush, turning local community halls and school grounds into centres of both aspiration and debate.

At a camp on the southern fringes of Kolkata, 28-year-old Subir Mitra, a commerce graduate preparing for competitive exams, said the allowance would not transform his life but might ease daily anxieties.”It won’t solve everything, but at least I won’t have to depend on my parents for every small expense while preparing for jobs,” he said.

Nearby stood Ritika Halder, a postgraduate in chemistry who has remained unemployed for nearly three years. She said the monthly assistance could help cover examination fees and travel costs for interviews.

“People assume educated youths won’t stand in line for this amount. But when there’s no steady income, every bit counts,” she said.

At a camp in coastal Kakdwip, a young mother, Mousumi Jana, waited with her toddler in tow. Married soon after school, Jana said she had resumed studies recently.

“This will help me buy books and continue studying without adding pressure on my family,” she said.

Officials across districts described the turnout as unprecedented, with lakhs registering within the first days of the drive.

For the ruling camp, the lines reflect public trust and outreach. For the opposition, they reveal a deepening employment crisis.

The TMC argues the cash support is a safety net for youths navigating a sluggish job market, while the opposition BJP has labelled it an election-time “dole.”

Leader of Opposition Suvendu Adhikari questioned the need for physical camps instead of a fully digital application process, alleging that the “exercise was geared more towards political mobilisation than helping the unemployed youths.”

“It also reflects that the TMC government despite being in power for the last 15 years, has failed to generate employment,” he said.

The state government rejected the charge.

Finance Minister Chandrima Bhattacharya said welfare schemes would continue despite fiscal constraints and accused the Centre of withholding dues.

Political observers noted that the camps have also acted as organisational exercises for the ruling party’s grassroots network.

Local councillors and booth-level workers were visible at several sites assisting applicants, a reminder of how welfare delivery and electoral mobilisation often overlap in Bengal’s political culture.

Political analyst Biswanath Chakraborty said the optics were significant.

“In Bengal, welfare programmes carry political messaging. The government is signalling empathy with unemployed youth while demonstrating administrative reach ahead of polls,” he said.

Not everyone standing in line was convinced.

At a camp in North 24 Parganas, Sabyasachi Dey, a B.Ed graduate, said he registered reluctantly.

“What can Rs 1,500 do today? We want jobs, not token support. But when opportunities are scarce, you take whatever help you can get,” he said.

An elderly woman collecting forms for her son, who now works outside the state, echoed a common sentiment.

“Any support helps, but every parent still wants their child to come home with a real job,” she said, reflecting the deeper social reality of persistent unemployment among educated youths.

The Rs 5,000-crore allocation for Yuva Sathi adds to a portfolio of welfare schemes that has defined the Banerjee government’s governance model, from women-focused cash transfers to farmer assistance programmes. The expansion of direct benefit transfers has helped the ruling party build strong voter linkages, particularly among economically vulnerable sections.

Critics, however, argue that recurring cash transfers risk obscuring structural concerns such as industrial stagnation and migration of skilled workers.

For many youths themselves, politics feels secondary.

As 24-year-old aspirant Debayan Sarkar said while adjusting his folder of documents, “People can call this politics or welfare. For us, it simply means a little support until work finally comes.”

With Assembly polls just months away, images of long queues, with young men and women waiting patiently with forms in hand, are already shaping the political narrative.