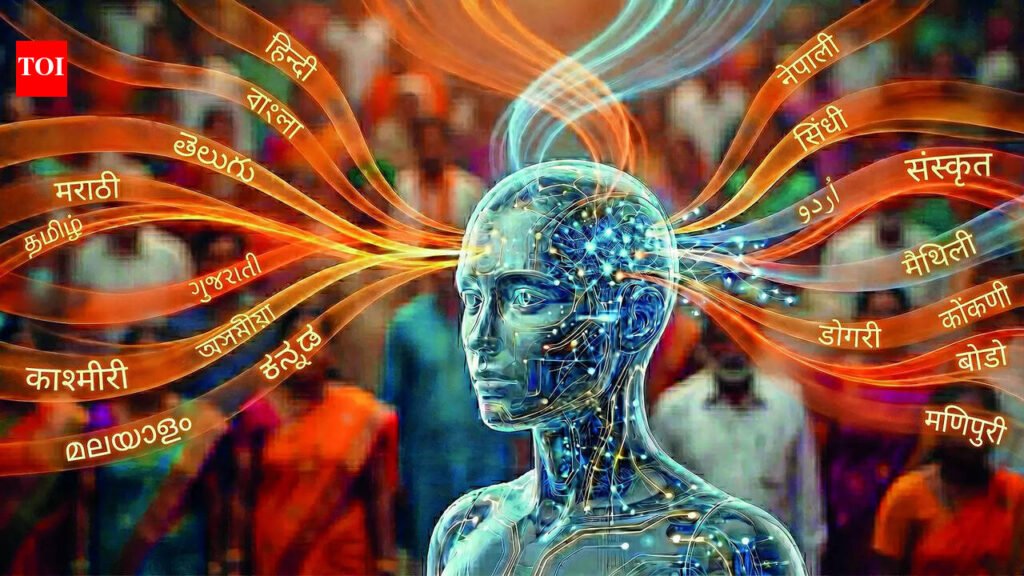

At Dhirubhai Ambani University (DAU) in Gandhinagar, doctoral student Bhargav Dave is doing something quite tedious: matching words. Gujarati to English, English to Gujarati — medical terms, one by one, fed into an artificial intelligence system that is gradually learning to speak the language. Hriday, the Gujarati word for heart, maps cleanly to its English equivalent. Pancreas, on the other hand, becomes “swadupind” — a translation that carries the weight of careful deliberation. “There are ground rules,” Dave explains. “The word ‘doctor,’ for instance, will not be rendered as ‘tabib’ or ‘daktar’. Similarly, medical terms like bronchial carcinoma, a variant of lung cancer, will not be given convoluted translations. So far, nearly 2 lakh such translations have been completed for Gujarati alone.” Dave is a member of the huge team dedicated to the Gujarati component of Bhashini, a nationwide project that brings together software developers, computer scientists, linguists and language experts under one roof. Their collective mission: to teach AI not only to recognize Gujarati word patterns but also to translate fluidly between Gujarati and other Indian languages. The project comes into sharp focus with conversations around AI’s impact on linguistic diversity growing louder. Bhashini — an acronym for BHASha INterface for India — operates under the National Language Translation Mission (NLTM), spearheaded by the ministry of electronics and information technology (MeitY). Its ambition is nothing short of making artificial intelligence work for every Indian, in their own tongue. Bhashini’s core team gathered recently at DAU to review four years of work as the initiative reached a significant milestone. With both an app and a website now live, the team took stock of what has been achieved and mapped the road ahead. Krishna Kishore, deputy director at MeitY for the NLTM, said that the central purpose is to bring all 22 scheduled languages of India into the digital ecosystem. “The primary idea was to make all Centre-run websites and platforms accessible in every language. Many implementations are already visible across websites. But beyond those, certain key areas such as law, agriculture, e-governance etc., require special focus. Multiple teams across India are working with that domain-specific lens,” he said. Translation is only part of the story. “The focus is equally on pragmatics — it should not only convey the literal meaning but should also make the context clear. The use of Bhashini has been successfully demonstrated at events like the Maha Kumbh,” he added.

The team that met at DAU

Experts associated with the project said that one of its focus areas is data sovereignty — keeping user data within Indian systems rather than routing it through foreign servers. The platform is also designed to be voice-native, allowing users to interact directly through speech, without needing to type a single word. Recently, at the India AI Impact Summit 2026, MeitY unveiled VoicERA — an open-source, end-to-end Voice AI stack. Govt departments can now quickly deploy voice-enabled citizen services in areas such as agriculture advisories, livelihood services, grievance redressal, citizen feedback, and scheme discovery. Prof Dipti Misra Sharma, a computational linguistics expert from IIIT Hyderabad and chief investigator for the Indian Language to Indian Language Machine Translation (IL-IL MT) initiative, offers a window into both the scale and the complexity of the work. “About 12 institutions have been associated with this project for four years now. Some of the basic models already existed, but the quality of translation was not satisfactory. Bhashini is unique due to its scope — unlike general-purpose large language models, here each language is given richer, more focused data. Moreover, languages with limited online presence such as Dogri, Bodo, Maithili are also included,” she says. The diversity of India’s languages presents a challenge and an opportunity, she notes. “We increasingly encounter mixed-language usage such as “Jab We Met”. How to train a model to translate that? These were the questions we wrestled with when working on the project. To give a sense of the computational scale involved, a supercomputer, Param Siddhi AI at C-DAC, was deployed for the task,” she adds.Need for Green AI In his presentation to the DAU gathering, Prof. Majumder made an urgent pitch for edge-native, low-energy, human-centred AI as a global public good. “The dominant model of AI today is energy-intensive, dependent on massive computational infrastructure and large proprietary datasets. For a country like India, what we need is a small, optimized automatic speech recognition model for indigenous languages — one that can run directly from a phone,” he said. “It should work offline or with minimal connectivity, consume low energy, and protect user privacy. That’s what will genuinely enable access to education, govt services, and information in a speaker’s own language.” A new lease of life for Dogri Dr Preeti Dubey, assistant professor of Computer Applications at Government College for Women, Udhampur, represented the Dogri language cohort at the DAU gathering. Compared to major Indian languages, she explained, Dogri enters the AI age with a thinner training dataset.“Like elsewhere in India, the Jammu and Himachal Pradesh region — home to the bulk of Dogri speakers — is seeing more children enrol in English-medium schools. Many learn Dogri at home, from parents or grandparents. For the project, we reached out to local libraries, converting physical pages to PDFs and then using optical character recognition to glean Dogri words and sentences,” she said. With a speaker base estimated between 2 and 5 million, Dogri’s inclusion in Bhashini represents a meaningful step toward preserving the language in an increasingly AI-dominated digital world — a model, experts say, of how technology can be turned towards linguistic conservation rather than homogenization. How AI learns to speak a new language The process by which AI acquires a language is fundamentally different from how a child does. Where a baby begins by mimicking sounds and slowly learns to connect spoken words to visual symbols, AI learns by detecting statistical patterns across massive datasets. At DAU, for instance, the team fed nearly two lakh Gujarati sentences from a wide range of sources into the system to build its foundational language model. Early efforts focused on legal, scientific, technological and administrative vocabulary. And rather than translating directly between two Indian languages, the system relies on what linguists call a pivot language. “If we give an input for translating Gujarati word into Bengali, the system first compares the Gujarati word to English or Hindi, which have far larger training corpora, and then maps that to Bengali, before generating the final translation. But for Bhashini, the larger goal is to improve direct Indian language-to-Indian language translation, and that demands much stronger parallel sentence data, rigorous evaluation and terminology control,” said one team member. A major part of generative AI involves predicting the next word in a sentence — an ability that only becomes reliable when the AI deeply understands a language’s syntax. This is where linguists become indispensable. They set terminology and style guidelines, review outputs for fluency and adequacy, and help the system navigate the natural variation in real-world usage. Gujarati, like most Indian languages, follows a subject-object-verb sentence structure — quite different from English’s subject-verb-object order — and teams must define a standard register while carefully documenting acceptable dialectal variations, from Surti to Kathiawadi, rather than imposing a single “correct” form. Finally, all data must be labelled and structured so that the AI can use it for interactive purposes — allowing native Gujarati speakers, for instance, to query govt repositories or converse with digital systems entirely in their own language. The building blocks Data collection: Models are trained on large monolingual corpora drawn from books, news websites, govt documents, online articles and voice samples, supplemented by parallel sentence pairs across language pairs. Cleaning and standardization: Scientists remove noise and duplicates, and normalize spelling, script, punctuation and formatting for consistency. Finding and teaching comparable data: The system first learns to match exact equivalent words across languages, then moves to structure and grammar. Source sentences are matched with the target sentences and quality checks are applied throughout. Tokenization: Words are broken down into smaller units called tokens, allowing the model to process each element individually and handle rare words and morphologically complex forms. Training the neural machine translation (NMT) model: — A transformer-based system is trained to transfer meaning at the sentence level, generating translations one token at a time. Employing neural networks: The neural network begins predicting the next word and completing sentences, improving in accuracy through repeated exposure to data. Beta testing and limited deployment: Once initial benchmarks are met, the model is connected to major databases and the broader internet, where it continues learning autonomously within defined parameters, developing a progressively deeper understanding of the language. Transfer learning and execution: The model learns from existing data through knowledge transfer (for example, from Hindi to Gujarati) on a multilingual platform at regular intervals. It is assessed through metrics and human review, fine-tuned for specific domains such as medical or legal, and then deployed. Ongoing updates enable it to incorporate feedback and support real-time training.