Travellers of the Renaissance era praised Goa’s goldsmiths as unmatched in skill, even outshining their European counterparts. This acclaim, enhanced by the influx of imported gold, turned local artisans into global talent

Long before Goa became synonymous with beaches and churches, Renaissance travellers described its goldsmiths as the finest in the world, surpassing even their European counterparts. Gold did not originate in Goa. It arrived from centres such as the Kolar gold fields and was transported to the port by traders along with gems and other precious materials.“The travel of these objects is why the term ‘Golden Goa’ acquired its reputation during the Renaissance period,” Tennessee-based art historian, Kelli Wood told TOI.

This reputation is embodied in the story of Raulu Chatim, the only named Goan goldsmith to be consistently cited in 16th century art histories. “He was recognised for his extraordinary skill soon after the Portuguese conquest and taken to Lisbon to work for King Manoel I for four years before returning to Goa, where he was awarded a pension and the rare privilege of owning a horse,” Wood said.His work, and the broader craftsmanship of Goan goldsmiths, fed international demand for jewellery, Goa stones, bezoar-like composite objects set in elaborate mounts, and other luxury artefacts exported eastward and westward.Remembering unnamed makersWhile figures such as Chatim entered European records by name, countless artisans remained anonymous.“There is a tendency, when we speak of or visit ancient monuments and see precious objects, to remember stories of kings, queens and empires, but seldom the makers, the artisans whose labour and ingenuity created these artefacts,” said Leandre D’Souza, creative director at Sunaparanta Goa Centre for the Arts.Developed in collaboration with Goan artists and researchers, ‘Makers & Materials’ attempts to reconstruct a history in which countless artisans and craft communities remained unnamed, even though their techniques continue to survive in local practice.Materials, ecology and craft“Red laterite bricks, white lime, shell windows, gilded statues, and the co-mingling of palm, salt, sea and air, Goa’s artistic landscape has been shaped by centuries of makers working in tune with the rhythm and ecology of the Konkan coast,” Wood said.An expert in Italian Renaissance and Baroque art, Wood encountered works from Goa during a group visit to the Pilar Seminary Museum. Its rare collection includes bangles, temple jewellery, bells and architectural fragments, viewed alongside collections at the Museum of Christian Art, Old Goa. Together, these allowed the team to imagine Goa as a major centre of artistic production.She said she became engrossed in understanding how builders, metalsmiths, carpenters, painters, gilders and sculptors collaborated across religions, communities and political regimes.“We looked back as far as the Kadamba, Vijayanagara, Bahamani and Adilshahi sultanates in pre-Portuguese Goa to trace innovations in metalwork within Islamic communities and building practices and sculptural traditions within Hindu temple communities,” she said. “These processes kept coming together in Goa, which had a turbulent history of changing hands because of its strategic port and value. We wanted to reconstruct the art practices that existed before the Portuguese arrived and then see how these remained visible later.”

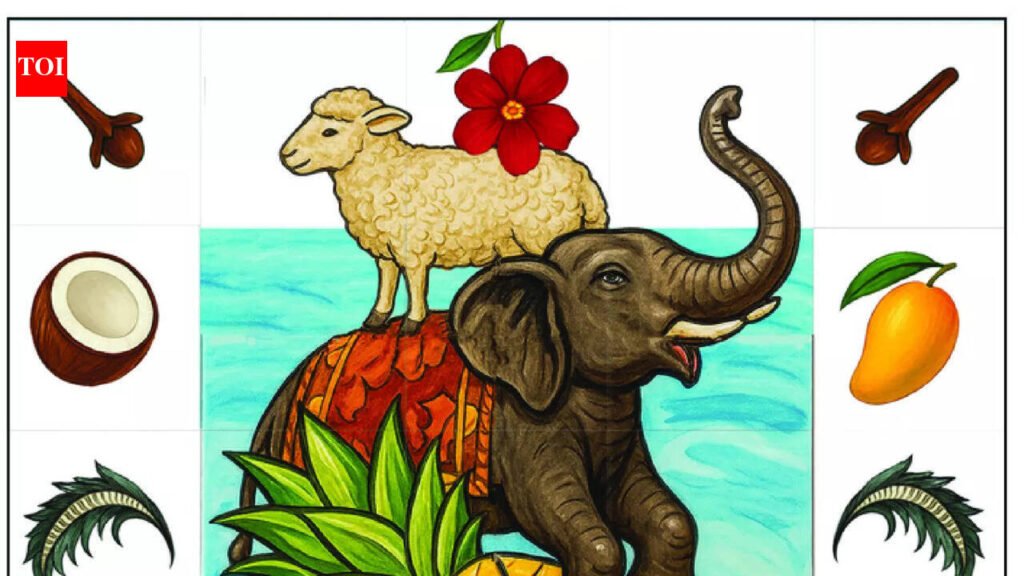

Wood’s research also highlighted how Goan builders and artisans relied deeply on natural resources, creating an ecosystem in which materials came from the soil and returned to the soil. Oyster shells, for instance, were not only used for window panes but also formed the basis of shell lime, the brilliant white plaster that continues to define Goan churches, temples and village houses. Juxtaposed with red laterite stone, shell lime gave Goa a distinctive architectural palette.“Shells are therefore essential to every part of the built landscape of Goa,” she said.She also studied historic routes used to transport stone and other materials, mapping sources of laterite, basalt and specialised building stones in relation to archaeological sites. “The findings show that Goa, over centuries, balanced the intense use of local materials with the import of specialised stone and metals,” Wood said.Belief, exchange and artistic languageGoan folklore holds that the mango tree was brought to the region by Lord Hanuman. This belief can be traced to the early 17th century, when a Konkani version of the Ramayana in a Portuguese manuscript claimed that Lord Ram had come to Goa and met village elders. The sacred origins attributed to ecological resources were closely tied to craft production and were not forgotten even after Christian conversion.Decorated wooden caskets and fall-front cabinets became popular with European merchants and missionaries in the 16th century. An Indian rosewood cabinet once housed in the Basilica of Bom Jesus, Old Goa, combines imagery and techniques from across the subcontinent, ranging from Mughal inlay to naga-like figures that form its feet. Similar iconography appeared in carved church pulpits. Gilt wooden naga-like angels once adorned the altar of the convent of Santa Monica, and Augustinian account books record payments not only to Christian architects and artisans, but also to Hindu sculptors and gilders, despite prohibitions on their working on church projects.“These objects should not be interpreted as merely adaptations of Indian forms for European purposes,” Wood said. “Craft communities understood how materials and styles conveyed complex local meanings through imagery, style and materiality, intertwining everyday and sacred experiences with their environment.”Despite the scarcity of surviving wooden or organic artefacts from pre-Portuguese times, Wood said techniques persisted through oral transmission and community practice.She also argued that conventional labels such as “Indo-Portuguese” fail to capture the complexity of Goan creativity. “Over time, Goa absorbed influences from Islamic metalworkers, Hindu temple builders, European visitors, travelling traders, enslaved artisans and migrant communities who brought their own methods and aesthetics. This artistic language is layered, hybrid and rooted in place,” she said.