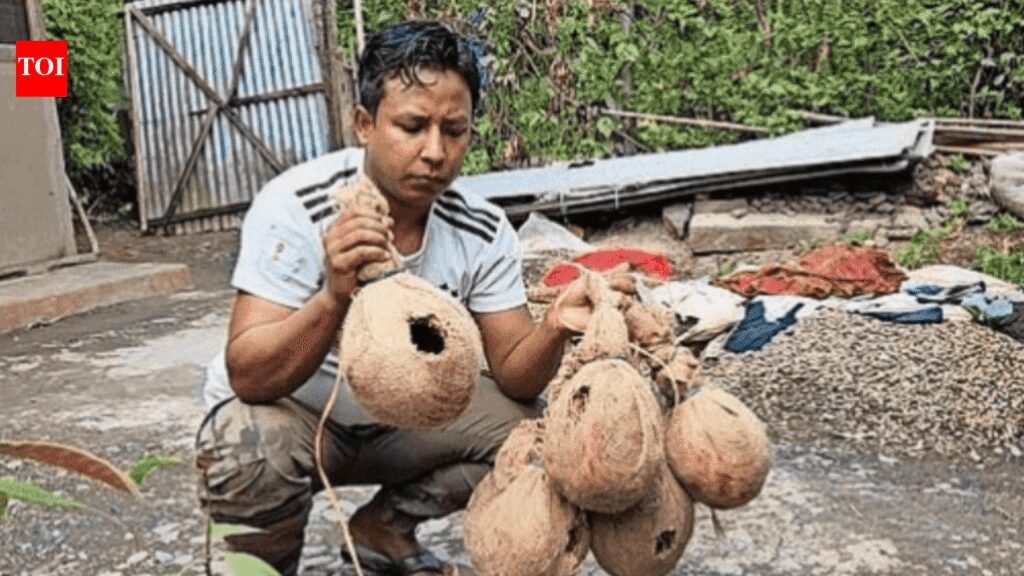

CHURACHANDPUR : Once common, now contested. House sparrows breed fast. Their habitats disappear faster. In conflict-scarred Manipur, survival depends on where a Rs 5 nest is hung — and who dares to hang it.The smallest birds face the biggest odds. As does Anish Ahamad. Gunfire can break without warning where he lives, along the taut seam between Churachandpur and Bishnupur districts. Step outside at the wrong moment and a walk can turn into a dash for cover.Still, when the clouds gather, Ahamad is on the move. He knocks on doors carrying handmade sparrow nests — round, pouchshaped, woven from natural fibre, light enough to hang on trees or walls. Gusty winds and heavy rain can erase months of nesting. The weeks before the rainy season are his rush hour. He shows families where to place nests, how to tie them, how to keep a fragile mission alive.This is year seven of ‘Save Sparrow’ — a rare constant in aregion ruled by uncertainty.Ahamad, an environmentalist from Kwakta village in Bishnupur district, has installed more than 600 nests and distributed nearly 300 for free. He estimates local sparrow numbers rise by about 5,000 a year.Timing is everything. “House sparrows have an extensive breeding season from March to Sept,” he says. “They are prolific breeders, capable of producing two to four, sometimes five broods a year.” A nest costs under Rs 5 to make.Sparrows are small but strategic allies for farmers. They eat crop pests and larvae during breeding season, reduce reliance on chemical sprays, and signal ecosystem health around fields and homes. Their decline tracks pesticide use, loss of hedges and cavities, and concrete sprawl. Bringing sparrows back means fewer insects in crops, better pollination conditions, and steadier yields at low cost.The work unfolds against violence. Since 2023, ethnic conflict between Meiteis and Kukis has repeatedly stalled his rounds. Ahamad is a Meitei Pangal. Staying safe often means staying indoors.“Due to the unfortunate events, I had to go without venturing out to work for a week,” he said. “At certain points, I needed to move to other places for safety.”At his home near the district border, danger can erupt anytime. “Conflicting parties frequently engaged in fierce gunbattles,” he said. “We used to get caught in the crossfire if we ventured out carelessly. Under such circumstances, it was very hard to keep on looking after the birds.”Recognition has not brought relief. Ahamad received the State Wildlife Incentive Award in 2022 and 2023, yet he works largely alone, with thin finances. “The love of environment and passion for wildlife conservation made me go on,” he said, frustration trailing the pride.Some households asked why sparrows mattered when livelihoods were strained. Many of those same villages now call him first, asking for nests and guidance.The ledger of work is long. Over years, Ahamad has handed more than 35 wildlife species to the forest department, planted 2 lakh saplings, and distributed 50,000 for free under his green cover initiatives.The mission began as a promise, bound to the memory of his late father, Abdul Ajij. As monsoon winds rise across the contesting hills and valleys, it returns as a public act — a man threading nests through fear, insisting coexistence is daily work, done before the rain and despite the guns.