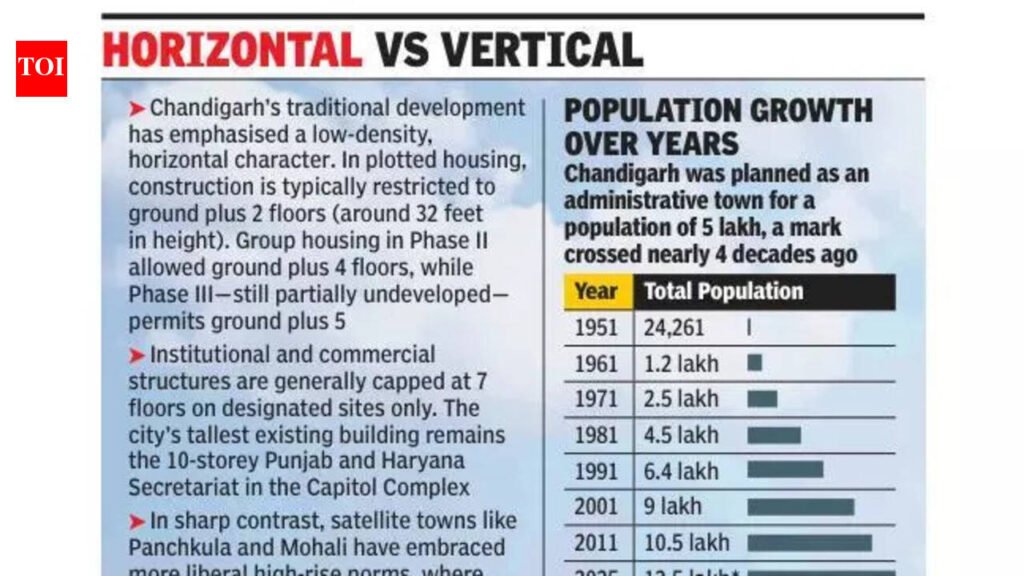

Chandigarh: Chandigarh, long celebrated for its iconic low-rise, horizontal urban design envisioned by Le Corbusier, is gearing up for a major evolution in its built landscape. The Chandigarh administration is moving towards permitting higher-rise construction in the city’s southern and peripheral sectors to better utilise scarce land amid rapid population growth and mounting housing demands.UT chief secretary H Rajesh Prasad told TOI that “periphery vertical expansion” represents the essential path forward to address the city’s developmental requirements, given the severe constraints on available land for new projects. He stressed that the heritage core—Sectors 1 to 30—will remain strictly protected and untouched by these changes.Prasad explained that the administration is considering greater flexibility in allowable building heights across residential, commercial, and institutional categories in the peripheral areas. “Holistic development of the city is a priority,” he said, adding, “ensuring healthy generation of housing, employment, and income within laid-down heritage, safety, and environmental parameters, and the apex court directions.”The proposed high-rise policy will go hand-in-hand with significant upgrades to supporting infrastructure in the affected zones. While a comprehensive high-rise framework is still being finalised, the administration indicated in principle that construction norms in Chandigarh’s peripheral sectors will broadly align with those already in place in the neighbouring cities of Mohali and Panchkula, where taller buildings are more common.This shift aligns with central govt directives to optimise land use in the UT. The administration is actively reviewing and deregulating several building controls, including floor area ratio (FAR), ground coverage, and height restrictions. A dedicated committee led by the Deputy Commissioner was formed to study these elements in detail. Additionally, minimum land requirements for educational institutions are under examination to enable more efficient development.Under the emerging approach, the UT administration will prioritise robust infrastructure creation while shifting the bulk of housing and land development responsibilities to the private sector. “The administration will act as a facilitator,” Prasad noted. “Land will be auctioned at market rates through fully transparent e-auctions. Liberal FAR and ground coverage provisions will be introduced to make housing affordable.“The initiative arrives against a backdrop of chronic housing shortages. The Chandigarh Housing Board (CHB) saw limited new supply, with its most recent general housing scheme dating back to 2016 and offering just 200 flats.BOX1: Horizontal v/s vertical characterChandigarh’s traditional development has emphasised a low-density, horizontal character. In plotted housing, construction is typically restricted to ground plus 2 floors (around 32 feet in height). Group housing in Phase II allowed ground plus 4 floors, while Phase III—still partially undeveloped—permits ground plus 5.Institutional and commercial structures are generally capped at 7 floors on designated sites only. The city’s tallest existing building remains the 10-storey Punjab and Haryana Secretariat in the Capitol Complex.In sharp contrast, satellite towns like Panchkula and Mohali have embraced more liberal high-rise norms, creating visible differences along Chandigarh’s borders, where taller structures rise against the city’s uniform low skyline.The Chandigarh Master Plan 2031 already lays the groundwork for such changes in select areas, including provisions for multi-rise (10-12 storey) mixed-use development along the 7.5 km Vikas Marg stretch, envisioned as a transit-oriented hub spanning 230 acres for residential, commercial, and institutional uses.BOX2: Relentless demographic pressureOriginally designed for a population of about 5 lakh, Chandigarh now houses well over 12 lakh residents.Much of Chandigarh’s population surge was accommodated in sprawling rehabilitation colonies on the city’s outskirts. These areas are often densely populated and continue to grapple with longstanding deficiencies in basic amenities and infrastructure.Nearly half of the city’s residents—approximately 50%—reside in rented accommodation, highlighting the severe constraints on homeownership options within Chandigarh proper. This rental dependency poses particular difficulties for long-term residents, including many who struggle to purchase or secure a home upon retirement, owing to the lack of a vibrant primary housing market and sharply rising affordability barriers.The acute shortage of affordable owned housing inside the Union Territory spilled over into neighbouring areas, spurring rapid real estate growth in satellite towns like Zirakpur and Kharar. These locales experienced significant growth, largely propelled by Chandigarh-based families and professionals seeking more attainable homeownership opportunities while remaining in close proximity to the city for work, education, and urban conveniences.