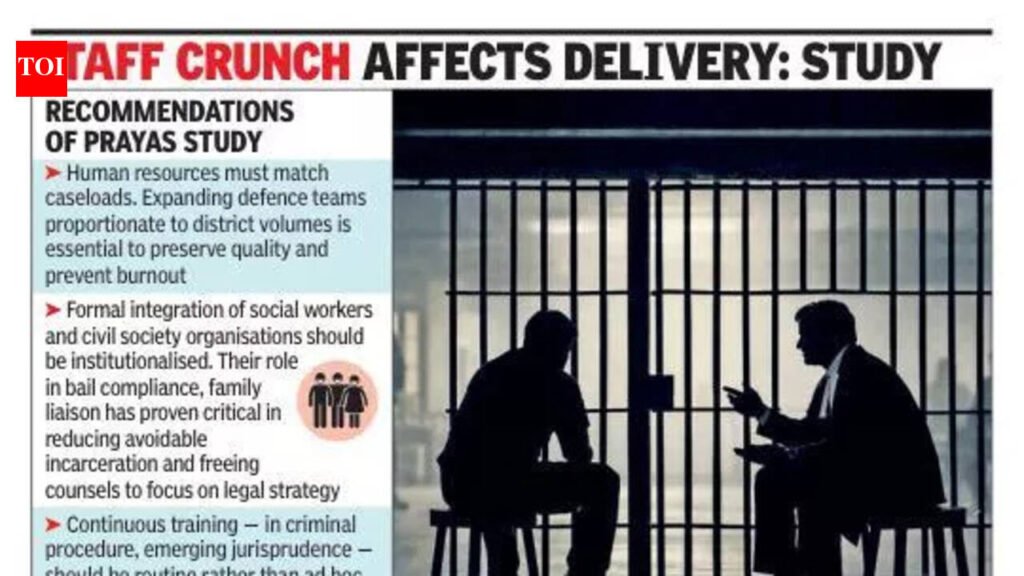

Mumbai: When 43-year-old Khajappa Nagore was acquitted in a high-stakes MCOCA case, he did not walk free. Instead, he spent an additional five years behind bars simply because he could not afford a Rs 50,000 bail bond. It was only through the relentless intervention of the Legal Aid Defense Counsel System (LADCS) — which fought for a bail reduction to Rs 25,000 and bridged the financial gap by coordinating with an NGO, that the gates finally opened for a man already proven not guilty.For decades, lawyers appointed through the Legal Services Authorities Act of 1995 were largely dismissed as a desperate last resort. It was defined by overworked panel lawyers and meager honorariums — sometimes a dismal Rs 900 for an entire case. However, a systemic revolution is now unfolding. A recent study by Prayas (TISS) reveals that the 2023 introduction of the LADCS is fundamentally reclaiming justice for the country’s 4 lakh under-trial prisoners. LADCS has handled almost 10,000 cases so far.A 66-year-old accused, in jail for almost a decade, recently secured bail from the Bombay High Court in a matter in which he was handed a ten-year sentence by the lower court. He recalled the stark difference in treatment. “I was told I didn’t even have to pay a rupee for the document copies. The lawyer stayed in touch with my wife and met me too in jail and ensured that I got bail.”Before this shift, legal aid relied on private “panel advocates” who often sidelined free cases for higher-paying clients or harassed the vulnerable for money. The LADCS has shattered this cycle by establishing a dedicated office of full-time professionals earning salaries between Rs 30,000 and over Rs one lakh, ensuring their absolute focus remains on criminal defense. Operating under a rigorous three-tier hierarchy of Chief, Deputy, and Assistant Counsels, the LADCS brings a structured approach to litigation.While undertrials were previously reluctant to accept legal aid, there is today an increasing demand for LADCS representation. Advocate Samyak Gimekar, Chief Legal Aid Defense Counsel in Mumbai, noted that the journey wasn’t easy. “Initially, undertrials refused to share even their chargesheets…when we used to visit jails, the biggest challenge was to explain that we are different from public prosecutors and we are to represent you. The accused were under the impression that since the lawyers are being provided by the state, they are people of the state. We had to tackle misconception. Yes, both public prosecutors and the lawyers under the LADCS are both governed by state, but they are different wings. This is the new office that is only concerned with representing the accused,” Gimekar said.As results became visible, word of mouth traveled through the barracks. “I have been in jail for almost a decade. Initially, I had my own lawyer because I was afraid Legal Aid lawyers would not be able to help. He charged me Rs 2 lakh. I managed to give him the money with the help of whatever savings I had. But suddenly he left the case after we had a disagreement. I was stranded… Thankfully I managed to secure a lawyer through the new system. He helped me secure bail.”Despite the success stories, the TISS study highlights that the scheme’s impact is constrained by persistent capacity gaps. The most immediate problem is understaffing, said Vijay Raghavan, professor, Centre for Criminology and Justice, School of Social Work, TISS and Project Director, Prayas-TISS. “In several districts, a small cadre of salaried defence counsels is responsible for an unmanageable volume of cases. While the entry of LADCs has definitely enriched the delivery of legal aid services for undertrials, the lack of sufficient number of LADCs, especially in big cities like Mumbai, leaves limited time for thorough preparation, sustained client engagement, or follow-up beyond urgent bail matters.”According to the TISS study, the strain is most visible at the level of the Chief Defense Counsel, a role that combines courtroom advocacy with administrative management, monitoring, mentoring, and reporting—functions that compete for attention and energy. While Gimekar manages 311 sessions trials alongside administrative duties, his deputies face even heavier volumes. Advocate Praveen Pandey handles 514 matters, advocate Shakuntala Sharma has 478, and advocate Lata Chheda manages 396.Infrastructure deficits further weaken delivery.“Many LADC offices lack adequate space, clerical support, and digital case-management systems. The absence of reliable, integrated documentation comes in the way of case tracking and contributes to delays in bail communication, court updates, and coordination with prisons and families,” the study noted.Access also remains uneven, added Prof Raghavan. District headquarters have benefited most from the scheme, but taluka courts and prisons continue to be relatively underserved. Time and travel constraints limit engagement in Sessions Court matters and serious offences, inadvertently skewing attention towards cases that can be processed quickly rather than those that require sustained defence.Coordination gaps persist across institutions. Limited routine engagement between defence counsels, prison authorities, police, and courts leads to procedural delays. While review meetings exist, stakeholders caution that monitoring risks becoming mechanical unless it meaningfully examines quality of representation and case outcomes rather than numerical performance alone. Finally, beneficiary mistrust remains a residual challenge.The study shows that the trust factor is steadily increasing among undertrials and prison officers about the efficacy of LADCs, decades of uneven legal aid delivery in taluka places under the empanelled system have shaped expectations. Structural reform alone has not fully dispelled the perception that free legal aid is slow, distant, or ineffective, the research said.