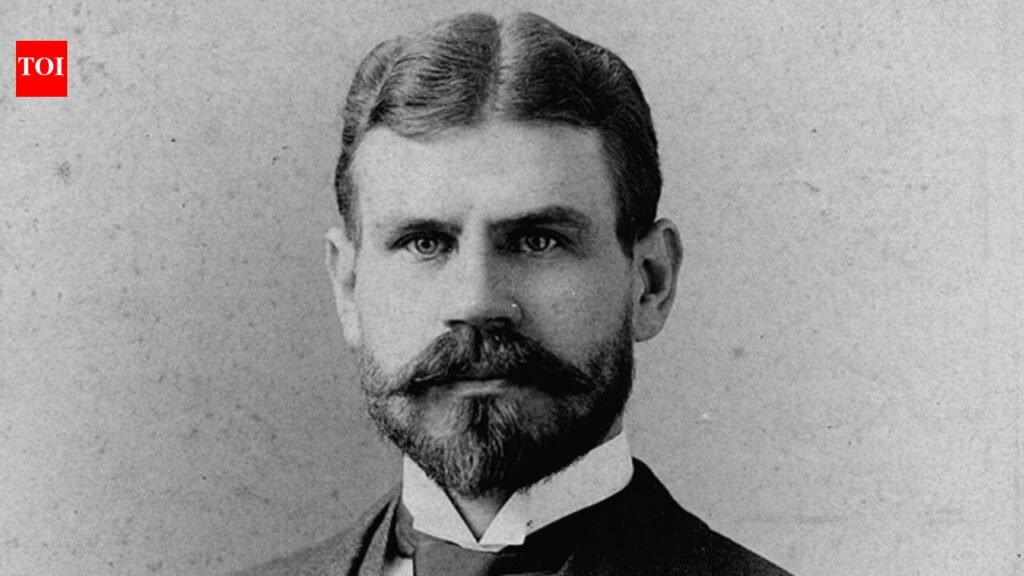

On 25 September 1900, Dr Jesse William Lazear died of yellow fever in Cuba. He was 34 years old. He left behind a wife in Maryland, a one-year-old son, and a newborn daughter who would never meet him. Lazear was not a reckless thrill-seeker or a fringe experimenter. He was a trained physician and epidemiologist, educated at Johns Hopkins, working as part of a formal US Army investigation into one of the deadliest diseases of the nineteenth century. What makes his death extraordinary is this: he allowed himself to be bitten by a mosquito that had fed on a yellow fever patient. Whether the infection was fully intentional or the result of laboratory exposure remains debated. What is beyond dispute is that his illness became pivotal evidence in proving that mosquitoes transmit yellow fever, a breakthrough that reshaped public health and made large-scale projects like the Panama Canal possible.

Yellow fever: the disease that terrified cities

Yellow fever did not originate in the Americas. It emerged in the rainforests of Africa and was introduced to the Americas in the 16th century through European colonisation and the transatlantic slave trade. In the so-called “New World,” it thrived in the balmy tropical and subtropical regions of South and Central America and the Caribbean, where climate conditions and mosquito populations allowed the virus to flourish. The disease struck unpredictably. After an incubation period of roughly three to six days, victims developed high fever, chills, severe headache, back pain, nausea and vomiting. In around one in five cases, the illness progressed to liver damage, causing jaundice, the yellowing of skin and eyes that gave the disease its name. Internal bleeding could follow. Mortality rates were frightening.

Patients in Yellow Fever Hospital, Havana, Cuba c. 1899/ Library of Congress.

For centuries, outbreaks erupted in port cities. But it was the Spanish–American War of 1898 that forced the United States to confront yellow fever as a strategic threat. In Cuba, more American soldiers died from yellow fever and malaria than from Spanish bullets. The Army wanted answers.

The Yellow Fever Commission and a dismissed theory

In June 1900, the US Army’s Surgeon General sent a team to Cuba: Major Walter Reed, Majors James Carroll and Aristides Agramonte, and Jesse Lazear. Together they formed the Yellow Fever Commission. At first, they pursued the dominant bacteriological theory. Many believed yellow fever was caused by a bacterium called Bacillus icteroides, proposed by Italian researcher Giuseppe Sanarelli. The Commission investigated and concluded that the bacterium was a contaminant, not the cause.

The Yellow Fever Commission / Image: numismatistsofwisconsin

That failure reopened an older, controversial idea. In 1881, Cuban physician Dr Carlos Finlay had argued that yellow fever was transmitted not by direct human contact or contaminated bedding, but by mosquitoes, specifically of the Aedes genus. When Finlay presented his hypothesis at the 1881 International Sanitary Conference, he was dismissed. The idea sounded speculative and unproven. But by 1900, scientific thinking had shifted. British and Italian researchers had demonstrated that Anopheles mosquitoes transmit malaria. Vector-borne disease was no longer absurd. It was plausible. Lazear believed Finlay might be right. On 8 September 1900, he wrote to his wife: “I rather think I am on the track of the real germ.”

Self-experimentation and the fatal bite

The Commission’s early mosquito experiments were clumsy by modern standards but methodical for their time. Lazear had begun breeding Aedes mosquitoes, the genus Finlay had identified ,and feeding them on confirmed yellow fever patients. The team had already discovered a crucial detail: the mosquito could not transmit the disease immediately. It had to incubate the infection internally for several days before becoming infectious, what researchers called the “extrinsic incubation period.” Early attempts to infect volunteers failed because they had not waited long enough. When they corrected that timing, the results sharpened. James Carroll allowed himself to be bitten by a mosquito that had fed on a yellow fever patient and had completed the incubation period. Within days, he fell severely ill. He survived, but narrowly. To rule out coincidence, a young soldier with no previous exposure to yellow fever was also bitten under controlled conditions. He too developed the disease and recovered.

Lazear allegedly allowed himself to be bitten by a mosquito that had fed on a yellow fever patient/ Image: PBS

These cases strongly suggested that mosquitoes were the vector. But ambiguity remained. Carroll had previously worked in a yellow fever hospital; he could, theoretically, have contracted the disease elsewhere. Then Lazear himself was bitten again. On or about September 13, 1900, Lazear was exposed to a mosquito that had fed on a yellow fever patient after the appropriate incubation interval. Whether this exposure was fully deliberate remains debated. The official account maintained that he was accidentally infected while handling experimental insects. However, Walter Reed later claimed to have found references in Lazear’s notebook suggesting intentional self-experimentation. That notebook remained in Reed’s possession throughout his career and reportedly disappeared shortly after Reed’s death, leaving the question unresolved. What is not disputed is what followed. Within days, Lazear developed symptoms consistent with yellow fever: fever, malaise, and progressive deterioration. On September 25, 1900, he died in Cuba at the age of 34.

Camp Lazear and the experiments That Settled the Question

Lazear’s death did not halt the work; if anything, it sharpened the Commission’s sense of urgency. In November 1900, it established an experimental station outside Havana named Camp Lazear, where two simple wooden buildings were constructed to test competing theories of transmission.In one, known as the “infected clothing building,” volunteers slept for weeks on bed linen deliberately soiled with the vomit, blood, urine and faeces of yellow fever patients, a direct attempt to test the long-standing “fomite” theory that contaminated fabrics and objects spread the disease. None of the volunteers became ill.

Members of the commission visit Carlos Finley in Havana | Roberto Ramos, Ramos Master Collection, Inc. via PBS

The second structure was the “infected mosquito building.” It was divided into two chambers by a fine metal screen. On one side, volunteers were exposed to mosquitoes that had fed on yellow fever patients. On the other, a control group remained protected from the insects but shared the same air. Nearly everyone exposed to the infected mosquitoes fell ill. None in the protected chamber did. The results ruled out both fomite transmission and airborne “effluvial” spread. The mosquito hypothesis was no longer speculation. It was demonstrated. In 1901, Walter Reed and his colleagues published their findings in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Reed’s name became synonymous with the discovery. To his credit, both he and Lazear had acknowledged Carlos Finlay’s original insight. But it was Lazear’s infection, and death, that gave the theory undeniable weight.

From discovery to public health revolution

Scientific proof is one thing; implementation is another. Major William C. Gorgas, the Army’s chief sanitarian in Cuba, was initially sceptical, but once ordered to act on the Commission’s findings he moved with methodical discipline. His teams screened patients to stop mosquitoes feeding on them, drained marshes, covered water containers, treated standing water with kerosene to kill larvae, and aggressively eliminated mosquito breeding sites. The result was swift. Havana, which from 1762 until 1901 had averaged at least one yellow fever case per day, was declared free of the disease within 90 days of sustained mosquito control. The implications were global. Yellow fever had long been one of the greatest obstacles to large engineering projects in the tropics. Controlling the mosquito population would later prove decisive in enabling the construction of the Panama Canal. A disease that had haunted port cities for centuries was rendered preventable not by a vaccine at first, but by vector control.

“The Conquerors of Yellow Fever”

The team’s work earned them widespread scientific and public acclaim; they became known as the “conquerors of yellow fever.” Walter Reed’s tombstone would later be inscribed with the words, “He gave to man control over that dreadful scourge, Yellow Fever.” Their contributions were further recognized in the Army Register, where the participants were listed annually in a “roll of honor.” Beyond the military, the 22 members of the establishment involved in the experiments received formal recognition from the U.S. Congress and the President, with living members, and the widows of those who had died—presented with gold medals.