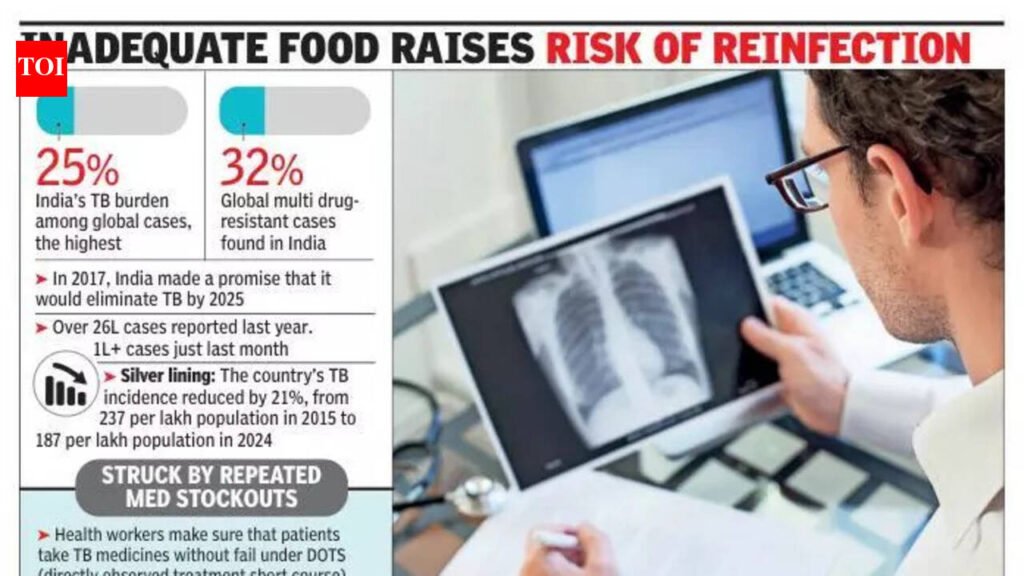

Mumbai: When 30-year-old Fatima (name changed) was diagnosed with drug-resistant (DR) TB in Jan last year, her doctors were clear: Missing a dose or skimping on nutrition wasn’t an option. The Govandi resident handed over her bank details to health workers, trusting the central govt’s promise of Rs 1,000 per month for nutrition. It was soon broken.Apart from two transfers of Rs 3,000 each in March and June, Fatima was left to fight the disease on an empty stomach for half the year. Like her, 39,164 patients in Mumbai were left high and dry all through 2025—India’s promised deadline for TB elimination—as just 9,800 were paid their dues. A TB specialist from Govandi, who has worked with top officials on several policy initiatives, said, “We now tell patients in the early stages of treatment itself that the money will eventually reach them, but we clarify there is no telling when.” Launched in 2018, Nikshay Poshan Yojana (NPY) was an acknowledgement that food intake is an essential part of TB treatment. At the time, Rs 500 per month was locked in as nutritional support; last year, this was increased to Rs 1,000. As per central TB division’s (CTD) latest data, 1.38 crore TB patients in the country have been paid Rs 4,453 crore since 2018. In the same period, 1.64 crore patients have been diagnosed, but over 26 lakh have been left out of the scheme. India reported as many fresh TB cases last year. CTD officials refused to comment. Soham (29) (name changed), a Thane resident, stopped receiving the sum long ago, after he asked for a change in his bank details. He was first diagnosed with multi-drug resistant TB in 2022 but missed his medication several times due to external circumstances. Standard drug-sensitive TB is treated for six months, while DR-TB treatment can last 18-24 months. Although the recently rolled out regimen shortens DR-TB treatment to just 6-9 months, it is yet to take over and cannot be given to extra-pulmonary TB cases. India reports around 1.3 lakh DR-TB cases annually and 15-20% of all TB cases are extra-pulmonary. By 2023, Soham had progressed to an extensively drug-resistant TB case. “I admitted myself to Sewri TB Hospital. The treatment and the food there helped. I was discharged last April at 56kg, but my lung was severely impacted.” The family’s finances took such a severe hit that Soham could not afford adequate food intake after discharge. By Oct, he suffered a reinfection. His weight dropped to 52kg; as of Saturday, it was 46kg. In Dec, his mother was diagnosed with DR-TB. Soham’s latest reports indicated he is now resistant to 13 vital drugs, including bedaquiline. Fatima has one toddler and a six-year-old to feed and just Rs 15,000 reaches home from her father’s tailoring job. Asked what she would have done with the monthly Rs 1,000, she said, “There is not much one can do with it, but I would have got at least some groceries, eggs and milk.” In her 200sqft inadequately ventilated home within Govandi’s slums, her mother pointed at her two children. “Any food she eats, the two nibble on it.” Fatima is immobile most days and can’t take the elder child to school. She worked at a school before TB struck. Public health specialist Chapal Mehra, convenor of Survivors Against TB, noted that the entire premise of NPY was to give patients access to these basic nutritional sources. “Loss of pay due to illness is common. It was straightforward: People should not be in a food crisis. Patients need items like eggs, milk, curd, and some fruits; they are widely available, easier to consume, and can aid in recovery.” Mehra and other experts had hoped for at least Rs 2,000 as monthly support. Dr Anurag Bhargava, whose landmark 2021 RATIONS trial was so influential in proving nutrition’s role in TB outcomes that WHO revised its global guidelines last year, noted that govt has provided no clear rationale for how it arrived at these figures. He questioned why the initial amount was set at Rs 500 and on what basis the increase to Rs 1,000 was considered sufficient. “India’s effort to provide such assistance to TB patients is likely the largest in the world. There are challenges in implementation which need to be addressed urgently. The timeliness, the amount that is disturbed needs a relook, which is likely happening at a national level,” he said. An ICMR-National Institute of Epidemiology study of over 3,000 TB patients found that while most received NPY funds at least once, there were delays exceeding three months. Patients who didn’t receive support were more likely to suffer poor treatment outcomes, the study said. Fatima estimates she has spent upwards of Rs 50,000 on her illness; she was earlier misdiagnosed with typhoid. Her weight was 54kg when she started TB treatment. As of her last checkup in the middle of the year, her weight had dropped to 50kg. The question lingers: If India’s own target of elimination has passed, what does it mean for 2030, the target for TB elimination as per sustainable development goals? Pulmonologist Dr Lancelot Pinto from Hinduja Hospital said, “We are nowhere close to meeting those goals. As long as there is overcrowding, increasing pollution—newer evidence links poor air quality and TB—and issues such as medicine stockouts and lack of nutritional allowance persist, TB is here to stay.“